The resistant Vercors

Introductory historical framework

The Vercors maquis (late 1942 – May 1944)

During the French Campaign (May-June 1940), the Vercors massif remained in the background of the fighting, even the Battle of the Alps which took place at its feet (Cluse de Voreppe). The inhabitants tried to acclimatise to the changes imposed by the French state, but a few isolated acts of disobedience were already evident in 1940. The reluctance was particularly strong among the socialists of the massif, who organised meetings in order, at first, to reconstitute their party clandestinely. In addition, a number of outsiders found refuge in the Vercors: students from several private Parisian high schools, young Poles, Israelites, or children from the Var in the canton of La Chapelle-en-Vercors from 1942 onwards.

After the introduction of the Relève in 1942, the creation of the Service du travail obligatoire (STO) in February 1943 forced many young Frenchmen to go and work in Germany. This contributed decisively to the creation of the Vercors maquis. At the end of 1942-beginning of 1943, a group of socialists from the Vercors, Eugène Samuel, Victor Huillier, André Glaudas, etc., in relation with militants from Grenoble, led by Dr Léon Martin and Aimé Pupin, gathered under the banner of the Franc-Tireur movement, organised, with the support of local relays, refugee camps for the refractory people: the first camp was set up at the Ambel farm in December 1942-January 1943. Several others were set up in the following months.

At the same time, Pierre Dalloz, an architect and mountaineer, imagined a strategic use of the Vercors, conceived as a natural citadel protected by ramparts formed by the cliffs. The aim was to create landing grounds to receive airborne Allied troops during a landing in the south of France, and then to cover the Germans’ rear. Jean Moulin and the general staff of Fighting France approved this project in February 1943; it was called the “Montagnards Project”. Pierre Dalloz then assembled a small team, including military personnel, to implement the project.

These two initiatives merged and a combat committee was set up, bringing together members of Franc-Tireur and initiators of the Montagnards project. The objective was to transform Dalloz’s project into a military plan and to supervise the maquisards’ camps in order to transform the refractory into combatants. After the arrests in the spring of 1943, which dispersed the first leaders (Martin, Pupin, Huillier), the responsibilities were shared with the designation of a civilian leader (Eugène Chavant) and a military leader with successively Alain Le Ray, in 1943, Narcisse Geyer at the beginning of 1944, and finally, François Huet from May 1944.

The local population gave the maquisards a great deal of support, which was essential for the survival of the camps; the La Chapelle gendarmerie brigade had the same attitude: after the Liberation, the brigade collectively received the Resistance Medal.

For the 300 or so men who joined the maquis during 1943, domestic chores, rounds, military training and long periods of waiting set the pace for life in the camps.

Allied parachute drops of arms and ammunition were essential to the existence of the maquis. The Vercors had seven approved airfields, the most important being the “Taille-crayon” airfield at Vassieux. The first parachute drop took place on 13 November 1943. To communicate with the Allies and fighting France, the maquis had to have radio teams, which were gradually set up from February 1943 in the Vercors, but the links remained fragile.

The maquis suffered several incursions by the occupying forces and the militia during the first half of 1944. They resulted in the death of maquisards and civilians: in January, in the hamlet of Barraques and then in Malleval; in March, in Saint-Julien-en-Vercors; in April, in Vassieux, with the arrival in force of the Militia.

The Vercors, liberated zone (6 June – 21 July 1944)

The announcement of the landing on 6 June 1944 caused euphoria in the region, as elsewhere in France, as the Liberation seemed imminent. In the Vercors, during the night of 8 to 9 June, the regional chief of staff Marcel Descour, who had just arrived from Lyon, gave the order to the military command of the Vercors, despite the latter’s reluctance, to proceed with general mobilisation. The order was implemented. Civilian companies as well as many young people, alone or in groups, climbed onto the plateau, the massif was “locked down” and its access routes controlled.

Between 9 June and 21 July 1944, the Vercors thus became a liberated zone with a dual command. The civil government was presided over by Eugène Chavant, whose main concern was supplies (rationing, supplies). As for the military command of the Vercors, it remained in the hands of François Huet, with Marcel Descour, regional military commander, setting up his regional headquarters in the massif.

On 3 July, at Saint-Martin, Yves Farge, commissioner of the Republic of the R1 region (now the Rhône-Alpes region), proclaimed the restoration of the Republic in the Vercors. As the Vichy regime had brought down the Republic, this restoration reflected a desire to establish a counter-state and to prepare for the future. In the Vercors, this restored Republic provided itself with the main services of a State: services to control movements at the exit points of the massif and the mail; repressive bodies with a military tribunal and a detention camp at La Chapelle, where German soldiers, militiamen, collaborators and also many simple suspects were imprisoned; communication tools with the publication of a newspaper, Vercors Libre and then Le Petit Vercors; relations with the outside world, in particular with the Allies, thanks to the reinforcement of radio teams.

Hundreds of men quickly arrived. On 11 July, all the young men of the Vercors aged between 20 and 24 were mobilised (around 400). By mid-July, nearly 4,000 men were gathered in the Vercors, the largest concentration of maquisards in the region. In this context, Commander Huet decided on 14 July to give a military structure to the Resistance in the maquis, assigning the maquisards to former French army units that had been reconstituted: the 6th, 12th and 14th Alpine Hunter Battalions, the 11th Cuirassiers Regiment, etc. Training and weapons handling exercises were intensified.

Allied parachute drops of weapons, some of which were carried out in broad daylight, notably on 14 July 1944 at Vassieux, resulted in the reception of several dozen tonnes of weapons. The Allies also sent several missions: the “Eucalyptus” mission (mission « Eucalyptus ») with a radio team; the “Justine” mission to train the maquisards in the handling of weapons; the “Paquebot” mission to prepare a landing strip at Vassieux…

The fighting in the Vercors (21 July – mid August 1944)

The Germans, worried about the high concentration of men in the Vercors at a time when the defeat of the Third Reich was looming, feared that these Resistance fighters might, during an Allied landing in Provence, carry out raids in the Rhone valley to hinder their withdrawal from the south of France. In order to remove these threats, after a few targeted attacks (battle of Saint-Nizier-du-Moucherotte (bataille de Saint-Nizier-du-Moucherotte), in the north of the massif, in mid-June), the German general staff prepared a general offensive against the liberated area of the Vercors, entrusted to General Karl Pflaum and called “Bettina”. With more than 10,000 men, it was one of the largest Wehrmacht operations against a maquis in Europe.

From mid-July, German troops deployed on the foothills of the Vercors, encircling the massif. Aware of the imminence of the attack, those in charge increased their requests to the Allies for reinforcements and heavy weapons.

The Resistance fighters on the outskirts of the Vercors tried to slow down the enemy pressure here and there.

On 21 July, the Wehrmacht launched an offensive with the simultaneous opening of four axes of attack: to the north of the massif, from Grenoble, the German soldiers seized the canton of Villard-de-Lans; at the end of the day, they were stopped at the hamlet of Valchevrière. Resistance fighters held this strategic sector for two days, but on 23 July the position fell, opening up the south of the massif to German troops.

On the eastern flanks, from the Trièves, mountain troops seized the numerous passes between 21 and 23 July. They thus crossed the imposing barrier of cliffs and progressed rapidly on the high plateaus.

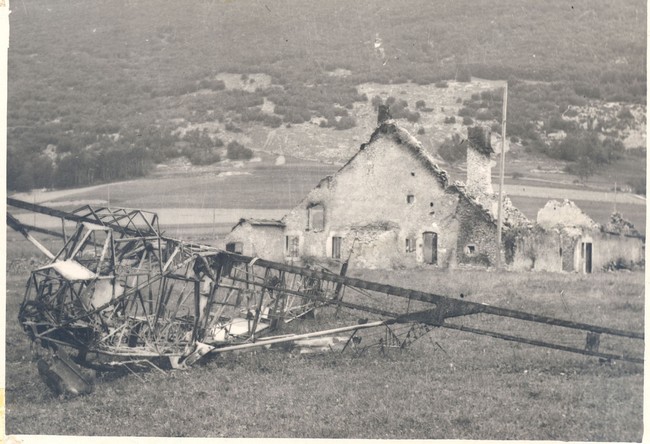

In Vassieux, the order was to strike quickly and hard, without sparing civilians, as the German general staff believed that the village was home to the Resistance’s supreme command. On the morning of 21 July, twenty-two German gliders landed on the outskirts of the village and the hamlets. On board were some two hundred men. A fierce battle ensued, complicated by the rain. It was only on 23 July, with the arrival of a second wave of gliders, that the Germans took control of the situation and forced the resistance fighters to end the battle of Vassieux.

Finally, the Zabel group of the 9th Panzer from Die reached Vassieux via the Rousset and Vassieux passes.

By the evening of 23 July, the fate of the Vercors was sealed. The German troops had gained decisive advantages on all fronts and were advancing throughout the massif. At the end of the afternoon, François Huet, military leader of the maquis, gave the order to disperse. The men had to stop fighting and “nomadize” by going into the forests.

The German soldiers were ordered to sweep the Vercors to track down the Resistance fighters and destroy their hideouts. Exactions multiplied: massacre of sixteen men in a farmyard at La Chapelle-en-Vercors on 25 July; destruction of the maquis hospital entrenched in the La Luire cave on 28 July; execution of twenty young men from the Vercors in Grenoble on 14 August, etc. Many farms were burnt down. Many resistance fighters managed to hide and survive in the forest. Among those who tried to leave the massif, some two hundred were intercepted at the foot of the Vercors by the cordon of soldiers surrounding the massif and then executed (Saint-Nazaire-en-Royans, Beauvoir-en-Royans, Noyarey…).

The German troops left the Vercors in mid-August 1944, leaving the massif in a state of total desolation. The human toll in the whole of the Vercors was heavy; several estimates have been made and the number of deaths is generally between 500 and 800, depending on the files, dates, geographical areas and conditions of death used. The material damage was considerable. In Vassieux, more than two hundred people lost their lives (including 73 civilians) and 97% of the buildings were destroyed. However, more than three thousand combatants survived and many of them took up the fight again, particularly within the 6th BCA and the 11th cuirassier regiment.

Assessment, end of the war, reconstruction and memory

On 15 August 1944, the Allied troops landed on the shores of the Mediterranean, in Provence. Alongside the Resistance fighters, many of whom were former Vercors maquisards, they quickly drove back the German troops: Grenoble was liberated on 21 August, the Drôme at the end of August and Lyon on 3 September. In March 1945, the allied forces crossed the Rhine. On 7 and 8 May, Nazi Germany capitulated unconditionally.

In the Vercors, as soon as the fighting was over, the populations had to deal with the emergency: a health emergency with the temporary burial of the victims; setting up the “system D” to be able to live in devastated villages, like Vassieux. There was a vast surge of national and international solidarity, fuelled by the strong reputation that the history of the Vercors maquis had acquired.

After the war, two phenomena marked the Vercors: the reconstruction of devastated villages, notably Vassieux, La-Chapelle, Saint-Nizier, taken in hand by the State, which imposed new principles of architecture and town planning on this rural society; the emergence of a memory of this “glorious and tragic” history which took shape around the creation of the Association of the Pioneers of the Vercors in November 1944, the awarding of the Cross of the Liberation to Vassieux in August 1945, the construction of necropolises and steles, annual commemorations, numerous publications of books, articles, testimonies, and, finally, the opening of the Resistance museum in 1973 and the Resistance memorial in 1994 in Vassieux.

In the Remembrance Hall of the Vassieux necropolis, the Pioneers had these words engraved by a Norwegian poet, a Resistance fighter who died in combat:

“We don’t want your regrets, we want to survive in your faith and courage.

Pierre-Louis Fillet

Director of the Resistance Museum of Vassieux-en-Vercors

From June 1940 to June 1944

This period, rich in events, can be entitled “From the defeat to the rise of the Resistance and the preparation of the liberating revenge”.

As soon as the Armistice was signed and a small army, known as the “armistice army” (of around 100,000 men) was built, soldiers from this army were busy hiding equipment under the noses of the Italian and German armistice commissions.

At the same time, in Grenoble and Villard-de-Lans, civilian teams, initially autonomous because of the need to remain underground, were considering the means to be used to reawaken the spirit of resistance to Vichy and then to Germany.

At the beginning of 1943, Pierre Dalloz imagined a strategic use of the geographical situation of the Vercors, which threatened the Germans’ communication routes and was correlated with an Allied landing in Provence, the Montagnards Project.

At the same time, the militia was created and the Germans decreed, with the complicity of Vichy, the Service du Travail Obligatoire (STO) (compulsory labour service), which was to send to the refugee zones of the Vercors those who refused to be forced to leave for Germany. They constituted one of the recruitment channels for the camps that spread throughout the massif; Ambel was the first example. The successive combat committees of the Plateau then had to transform these maquisards into fighters who were fed, equipped, armed and instructed in basic military skills. The parachuting of light weapons by the allies, and never heavy weapons, and the raids on the Chantiers de la Jeunesse shops only provided the maquisards with a minimum of equipment.

The Italians and then the Germans, aware of the progress of the Resistance, carried out raids on villages or suspicious areas. The militia did the same in the southern Vercors. While the former only carried out arrests, the Germans and the militia were responsible for exactions and massacres.

Authors: Guy Giraud and Julien Guillon

The first Resistance fighters

The first Resistance group in Villard-de-Lans was formed in 1941 around Eugène and Simone Ravalec, Théo Racouchot, Edouard Masson, Victor Huillier, Jean Glaudas, Marcel Dumas, Marius Charlier and Clément Baudoingt.

In 1942, these personalities were joined by others living in Lans, Autrans, Méaudre, Saint-Martin-en-Vercors and Pont-en-Royans. Among them, three women played a decisive role: Yvonne Ravalec, Denise Glaudas and Thérèse Huillier.

This original nucleus ratified its membership of the Franc-Tireur movement.

On 6 April 1942, Eugène Samuel contacted Léon Martin in Grenoble, thus establishing the first link between the Grenoble group (Eugène Chavant, Aimé Pupin in particular) and the Vercors group. The Huillier coach company facilitated the connections.

On 6 January 1943, Victor Huillier organised the Ambel camp in the Drôme, camp 1 of the massif, to receive those who refused to take part in the compulsory labour service (STO).

In 1943, the primary source of the Resistance joined the team of Pierre Dalloz, promoter of the Montagnards Project. Thus was born the first Vercors combat committee.

Author: Guy Giraud

Source :

Bulletin Le Pionnier du Vercors, n° 129, November 2014.

The birth of the Resistance in Vercors

The first Resistance fighters in the Vercors came from Villard-de-Lans. The names of the first nine Resistance fighters are inscribed on the plaque on the façade of the pharmacy in the Park. They include one woman and eight men.

Sociological observation of the group shows its diversity with regard to the professions and social level of those involved: a pharmacist, a doctor, a hotelier, a banker, a trader, a transporter, an electrician from Force et Lumière, a tax collector and a farmer.

Author: Guy Giraud

Source:

ANPCVV, Le Pionnier du Vercors newsletter, issue 19, Grenoble, November 2014, page 29.

The military project

The military project, known as the Montagnards Project, took shape throughout the Vercors after a slow evolution of the Resistance, from 1941 to 1944. Several phases can be distinguished.

The phase of isolated and parallel resistance initiatives:

The first groups met spontaneously on the massif, notably in Villard-de-Lans, on the initiative of the Huillier brothers, Eugène Samuel and Théodore Racouchot. In Méaudre, Georges Buisson “knew that something was going on in Villard” and wanted to make contact. In Royans, Benjamin Malossane, Jean and Louis Ferroul gathered their relatives to talk about the “events” castigating the Vichy regime and the armistice. At the same time (March 1941), Pierre Dalloz, in the presence of Jean Prévost, imagined the possibilities of using the massif in wartime.

The phase of organised resistance to parallel projects:

From the spring of 1942, from Grenoble, thanks in particular to Léon Martin and Aimé Pupin, the Franc-Tireur movement was to weave its web by relying on the existing groups on the massif. In December 1942, a “Note on the military possibilities of the Vercors” was written by Pierre Dalloz. It included a “Programme for immediate action” and a “Programme for further action”. This note, sent at the end of January 1943, via Yves Farge, to Jean Moulin, who gave his approval, became the “Montagnards Project”. Charles Delestraint, Vidal, head of the Secret Army (SA) on a national scale, validated this project and brought it to the attention of London. On 25 February 1943, the message “Les Montagnards doivent continuer à gravir les cimes” (The Montagnards must continue to climb the peaks) indicated that it had been validated by Free France.

The phase of merging the projects:

From February 1943 onwards, due to the influx of STO refractory soldiers, farms and hostels took in the latter who, being too numerous, had to be directed to other places, thus giving rise to the first camps organised by the civilians of the Franc-Tireur movement. In addition, at the beginning of 1943, Pierre Dalloz’s strategic idea emerged of making the Vercors an organised reception area for some 7,500 Allied parachutists who, guided by the 400 to 450 fighters in the camps, would act on German communications in support of a landing in Provence. Alain Le Ray conceived the military plan corresponding to the project. In March 1943, a survey of the massif was carried out by an initial team consisting of Pierre Dalloz, Yves Farge, Remi Bayle de Jessé, Marcel Pourchier and Alain Le Ray, in order to refine the project. After close contacts with Aimé Pupin (Mathieu) of the Franc-Tireur movement, initially for questions of camp supplies, the two teams merged. The isolated mountain camps contribute to bring density and concretization to Pierre Dalloz’s project.

The first tests:

This first team is quickly dismantled by the arrests made by the Italian political police, the OVRA: Léon Martin on April 24, 1943, Aimé Pupin on May 27, 1943. The links with Free France were also broken because in June 1943, Charles Delestraint and Jean Moulin were arrested. For his part, Pierre Dalloz went to Paris, then Algiers in November 1943, where he wrote a new, more complete note on the project to use the Vercors, drawing on the input from the camps created by the Franc-Tireur movement.

From refuge to combat :

A second combat committee, led by Captain Alain Le Ray (Rouvier), the military leader, and Eugène Chavant (Clément), the civilian leader, aimed to transform the refractory into combatants. In August 1943, at the Arbounouze meeting, the logic of dual command between civilians and soldiers was established.

Alain Le Ray, following reproaches from Marcel Descour (Bayard) concerning the lack of organisation of the November 1943 parachute drop at d’Arbounouze, resigned and became the head of the Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur (FFI) of Isère. Another important figure left the Vercors: Pierre Dalloz, who left for London and Algiers to defend his plan, without apparent success, did not return to the Vercors.

Eugène Chavant, exasperated, leaves for Algiers to obtain confirmation of the consideration of the Montagnards Project. The Central Intelligence and Action Bureau (BCRA) promised him orally that French paratroopers would be sent. Jacques Soustelle encouraged him with a written text and a large sum of money.

In the spring of 1944, the Vercors received numerous parachute drops of weapons and teams of agents from the inter-allied services to instruct the fighters in the handling of these weapons. One of them, which arrived at the beginning of July, was given the task of setting up a landing site at Vassieux-en-Vercors. Everything concurs so that Marcel Descour decides to mobilize the forces of Vercors after receiving the message of the BBC, June 5, 1944, “The chamois of the Alps leaps”, despite some reluctance of François Huet, partisan to wait for the launch of the landing in Provence, which nobody knew the date. In accordance with the provisions of Alain Le Ray’s plan, the Vercors was locked down with between 3,500 and 4,000 fighters instead of the 450 initially planned.

Authors: Julien Guillon and Guy Giraud

Source:

From “La Résistance en Vercors”, article by General Le Ray in Le Pionnier du Vercors, n° 71, Grenoble, ANPCVV, June 1990.

From the Montagnards Project to the military plan

It is worth analysing the criteria that underpinned the decision of the Vercors Government to anticipate the possible implementation of Pierre Dalloz’s Montagnards Project by implementing the military plan drawn up by Alain Le Ray on 9 June 1944, the date of the mobilisation of the Maquis forces.

Alain Le Ray set out the general procedures for blocking access to the Vercors. It was a question of ensuring the remote security of the Vassieux-en-Vercors landing ground to allow the expected landing of the allied parachutists, to regroup them and, without delay, to leave the massif to harass the Germans on the communication routes of the Rhone valley and the Alps road in connection with a landing in Provence.

Author: Guy Giraud

The civil and political project

Pierre Flaureau (Pel) of the Franc-Tireur et Partisans Français (FTPF) movement, of communist obedience, also known as FTP, at the instigation of the provisional government of the French Republic in Algiers, decided to bring together in Méaudre, on 19 January 1944, personalities of the Resistance in Isère, belonging to the various large movements as well as to the armed organisations: FTP, Secret Army (AS), Vercors maquis.

On the one hand, it was a question of defining a strategy of action against the occupier. The differences of opinion between the FTP and the AS, theoretically grouped under the name of Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur (FFI), led to stormy debates. The FTP, who were in favour of immediate insurrection whatever the cost in civilian casualties, were opposed to the ideas of the FFI, who instead advocated a waiting scenario aimed at supporting the Allied landings in France in due course; on the other hand, it was a question of appointing the future president of the Isère Departmental Liberation Committee and the future Commissioner of the Republic in Grenoble.

During this meeting, Eugène Chavant defended the originality of the Vercors in the department with regard to the national mission received from fighting France (the Montagnards Project).

Authors: Guy Giraud and Julien Guillon

Organising the Isère departmental committee for national liberation

In application of the directives of the provisional government in Algiers, a meeting was held in Méaudre on 29 January 1944 to define the composition of the Isère departmental committee for national liberation, its objectives and the means to be implemented.

The participants represented different local Resistance movements with diverse, if not opposing, political commitments and action tactics.

Due to the importance and sensitivity of the topics discussed, differences of opinion emerged. Nevertheless, the meeting made it possible to sketch out the future administrative organisation of Isère, particularly for Grenoble.

Author: Guy Giraud

Youth workcamps

The Chantiers de la Jeunesse were created on 4 July 1940. General Paul Marie Joseph de la Porte du Theil became its Commissioner General. The laws and decrees of 18 January 1941 set out the organisation and the status of the cadres. They were dissolved on 4 January 1944 to become a formation of supervised workers, intended to carry out work for the Germans. De la Porte du Theil was arrested. They came under the control of the Minister of Labour and Industrial Production, the technocrat Jean Bichelonne, an ultra-collaborationist, who was responsible for the implementation of the Obligatory Labour Service.

The armistice of 22 June abolished military service. It had to be replaced in order to supervise and keep a disorganised youth occupied in a healthy way. Young men, born between 1920 and 1924, were incorporated into groups organised from 1941 in the free zone, then in 1942 in the occupied zone as well as in North Africa. The training courses lasted eight months. The trainees were not armed. The aim was to replace the forbidden military service with an experience combining political training and moral and physical education through teamwork in camps in the middle of nowhere. Discipline is of the paramilitary type. The staff is made up of demobilised active or reserve officers. In order not to appear to the occupying forces as a disguised military organisation, the camps were placed under the supervision of the Secretary of State for National Education and Youth.

Around the Vercors massif were the following groups: n° 9 Monestier-de-Clermont, n° 10 Saint-Laurent-du-Pont, n° 11 Villard-de-Lans, n° 14 Le Diois, n° 15 Saint-Jean-en-Royans. Their shops are rich in supplies and various equipment. The Resistance, by trickery or with certain internal complicities within the groups, would make them a source of supplies (clothes, supplies, tents, skis, etc.).

When the Chantiers were disbanded, some of the leaders and young people joined the armed resistance in the maquis.

Authors: Julien Guillon and Guy Giraud

The Vichy concept of national revolution

The clauses of the armistice of 22 June 1940 abolished military service. The Vichy government decided to create the Chantiers de la Jeunesse (youth work camps), open in the free zone and in North Africa to young people aged 20. Developed as camps in the countryside, they were inspired by the organisation of life in scouting. The aim was to inculcate the values of the national revolution advocated by Vichy.

The relationship of the Chantiers with the Resistance was ambiguous. An anti-German state of mind permeated some of the leaders and young people. Well supplied with various materials, the camp shops were a source of supplies for the maquis.

Under German pressure, the Chantiers de la Jeunesse were dissolved on 15 May 1944 – the dissolution was ratified on 15 June 1944 – and most of the staff then joined the Resistance.

Authors: Julien Guillon and Guy Giraud

The maquis phenomenon

“The maquis! This word was first heard whispered, repeated in low voices in cities like Lyon, where the mountains are close by. A clandestine word like the struggle itself of the French people (…). The maquis was the newest phenomenon of the vitality and will of the French people. Far above the village, the maquis watches, watches, disperses, reforms, disappears, returns, attacks, (…) they are spoken of with pride and tenderness. The vast complicity of a whole people surrounds and supports them. Where do they come from, the guys of the maquis? The Germans and the filthy Vichy henchmen called them brigands and terrorists. I remember them in the Vercors, in Savoy.

I see their faces again: workers, students, peasants, craftsmen, employees, officers, of all classes and all conditions, of all beliefs and all tendencies. Gangs? Come on! A guerrilla army, certainly, but with its discipline, its brotherhood of arms, its honour, its flag…”.

This long quote1 is from the pen of Yves Farge (1899-1953). He was a journalist at the Progrès de Lyon, a Resistance fighter from 1941 onwards, president in June 1943 of the Comité d’Action contre la Déportation (CAD, responsible, among other things, for combating the STO and supplying the maquis), commissioner of the Republic of the Rhône-Alpes region in April 1944, president of the ceremony for the Restoration of the Republic in the Vercors on 3 July 1944, and liberator of the 800 hostage prisoners in Montluc Prison, including Maquisards. In short, this Companion of the Liberation by decree of 17/11/1945 was an actor and an informed witness of the “maquis phenomenon”, in its full development. The lyricism of his text forcefully describes the phenomenon of the “fighting maquis”, of the years 1943 and especially 1944 and for the Vercors of the “maquis mountain”. According to the terminology of François Boulet2, it is necessary to evoke first of all the “refuge mountain”, at the origin of many maquis: it collects the refractory to the STO, but also French or foreigners threatened in their safety. It developed – often near the villages – an “ethic of responsibility and “fraternity” with its “humanitarian values”.

The Vercors is fully in line with this approach of the “refuge mountain” – that of the camps – which gradually became the fighting “maquis mountain” – ultimately that of the reconstituted military units. However, it is clear that this path will not be “binary”, but in this chaotic period, will be strewn with many adventures, both happy and dramatic. It should also be noted that the behaviour of certain maquisards across the country was not always exemplary3.

Authors: Philippe Huet and Alain Raffin

Sources :

1- Jean-François Armorin, Le temps des terroristes, Paris, Editions Franc-Tireur, 1945, preface by Yves Farge ;

2- François Boulet, Les Alpes françaises, des montagnes refuges aux montagnes maquis,

Paris, Editions les Presses Franciliennes, December 2008 (pp. 356 and following);

3- Jacques Canaud, Le temps des maquis, Sayat, éditions de Borée, October 2011, p. 185.

The origins of the maquis

At the beginning, did the initiators of the Resistance imagine that they had to create shelters for people who were threatened or in an illegal situation? In the words of the historian Henri Michel, “The maquis was a gift that the occupier made to the Resistance”, since it was following the Relève and later the Service du Travail Obligatoire (STO) that it became necessary to provide shelter for “refractory” people. Thus, after 8 laws and 11 decrees promulgated by the French head of state between 4 September 1942 and 26 August 1943, and according to German statistics, more than 600,000 French workers out of nearly 850,000 requisitioned workers left for the German war factories until 30 September 1944.

Of course, not all the refractory workers joined the maquis, but there was a strong source of recruitment for the Resistance. However, it must be emphasised that the vast majority of these rebels were looking for a refuge rather than a combat base. Thus, according to the historian François Boulet, in the spring of 1943, 8 camps of 50 men each were formed in the Vercors.

Authors: Philippe Huet and Alain Raffin

Sources:

François Boulet, Les Alpes françaises 1940-1944: des montagnes-refuges aux montagnes-maquis, Paris, Les Presses Franciliennes, 2008, pp. 360 and following.

Alain Guérin, Chronique de la Résistance, Paris, Omnibus, 2010, p. 1057 and following.

Henri Michel, quoted by Alain Guérin in Chronique de la Résistance, Paris, éditions Omnibus, 2007, p. 1058.

Revue d’histoire de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale, n° 49, January 1963.

The camps, daily life – An attempt at synthesis

Keeping a group of men in the forest alive over the long term and most often in hiding is a permanent challenge that the camps had to resolve: security, health, supplies, physical and then military training, weapons, relations with the population, leisure time, so many issues to be resolved day after day.

The different aspects have been studied in various books, in particular Le Temps des Maquis by Jacques Canaud – Edition de Borée, 2011), using a similar grid.

The original and specific study of the Vercors presented here highlights the complexity of the description of an often nomadic life, in any case uncertain, which had to unite men of all ages, all motivations, all convictions – the witnesses who went to the end of the fighting will speak of a fraternity born between them for life.

Deliberately in the presentation, the choice was made to exploit the testimonies “as close to the ground as possible”, to try to grasp the daily reality of the adventure of the camps.

Authors: Philippe Huet and Alain Raffin

Source:

Jacques Canaud, Le Temps des maquis, Sayat, Edition de Borée, 2011.

The wait, the Italian, German and militia blows

Isère and Drôme, located in the free zone from June 1940 to November 1942, experienced two periods of occupation. The first, from November 1942 to September 1943, was that of the Italian troops. Indeed, after the Allied landings in Morocco and Algeria, Italy occupied the Alpine regions and Corsica.

The armistice of 3 September 1943 signed by Marshal Badoglio reversed the situation, causing the arrival in force of German troops throughout the country, particularly in Grenoble; this was the second period of occupation, lasting until August 1944.

The occupying forces, whether Italian or German, did not deploy permanent troops on the massif before the attack of 21 July 1944.

It is clear that it monitored the rise of the Resistance by infiltrating spies, engaging its observation planes and carrying out spot checks, often based on intelligence.

Italian forces, through the activity of the Organizzazione per la Vigilanza e la Repressione dell’Antifascismo (OVRA), the Italian political police, dealt some blows to the Resistance.

General Karl Pflaum’s 157th reserve division, supported by the entire German repression apparatus, proved more dangerous than the Italian repression of the inhabitants of the massif.

The Lyon militia made a devastating incursion into Vassieux-en-Vercors and La Chapelle-en-Vercors from 16 to 23 April 1944.

Authors: Julien Guillon and Guy Giraud

From the summer of 1944 to the Liberation

The period from 9 June to the Liberation was marked by the following events

- the mobilisation of the maquis, that of civilian companies and that of individuals or small less organised teams, the structuring of units,

- the blocking of the massif in accordance with the military plan drawn up by Le Ray,

- the fighting on 13 and 15 June (les combats des 13 et 15 juin) at Saint-Nizier-du-Moucherotte,

the euphoric phase at the beginning of July, which led to the restoration of the Republic in the Vercors and the organisation of a great ceremony for 14 July,

The German assault of 21 July was centred on Vassieux-en-Vercors in conjunction with attacks from the north (Quatre-Montagnes), the east (the Pas de la falaise orientale) and the south (Vercors drômois). The operation was completed by the sealing off of the massif’s exits leading to the Drac and Isère river cuts. Massacres of civilians and fighters followed, – The government then gave the order to disperse to the wooded refuge areas of the Vercors to survive the German sweep,

As soon as the occupying forces left, the fight for the Liberation resumed on an individual basis, but above all, by units (11th Cuir. and 6th BCA) within the framework of the amalgam.

Author : Guy Giraud

The Montagnards Project on trial, the events of June 44

The events that took place in June 1944 were the result of four major events:

- 0n 5 June, the FFI headquarters, made official on 9 June, issued the order to mobilise the Resistance in support of the Allied landing in Normandy. The green plan (sabotage of the railways) and the red plan (gathering of all the Resistance fighters) were activated on the national territory.

- Around 15 June, Koenig gave the order to curb guerrilla actions and avoid large gatherings of the maquis.

- M. Descour (Bayard), chief of staff of the R1 region, was convinced of the validity of the Montagnards Project; indeed, E. Chavant, back from Algiers, reported the verbal promises of the BCRA (Lieutenant-Colonel Constans, known as Saint-Sauveur, concerning the sending of 2,500 paratroopers on the Vercors, and a letter from Soustelle (head of the Directorate of Special Services in Algiers) specifying the validity of the directives of General Delestraint (Vidal) on the Vercors mission.

- Mr. Descour, as a disciplined military, ordered the mobilization of forces of the massif on June 9, overriding the reservation of F. Huet (Hervieux), the military leader of the Vercors, which recommends mobilizing only in accordance with the landing in Provence, whose date was unknown.

All the events of June contributed to the first fighting on 12 and 13 June at Saint-Nizier-du-Moucherotte (12 et 13 juin à Saint-Nizier-du-Moucherotte).

Authors: Guy Giraud and Julien Guillon

The balance of forces in the Vercors

The evaluation of the ratio of forces engaged in the Vercors by the belligerents results from the comparison of the evolution of their respective combat capabilities.

On a national level, from 1940-1942, the informal resistance, which would gradually take shape with the birth and growth of Resistance movements, was opposed by the respective forces of the Italian and then German occupiers and the French Vichy state.

As soon as the Germans invaded the free zone in November 1942, the armistice army was disbanded and the Vichy French state created the militia in 1943. The population, which was often wait-and-see because of its difficulties in coping with everyday life, gradually became anti-German.

Without necessarily tipping over in favour of the Resistance, the balance of power, unquestionably in favour of the occupier and its auxiliaries, tended to crumble, undermined by the beginning of the punctual actions of the free groups progressively set up by the Resistance against the soldiers and the infrastructure useful to the occupier.

In 1943, the compulsory labour service (STO) was decreed. Those who refused to take part in this service went to refugee zones. They formed the framework of the future armed resistance. In the Vercors, civilians and soldiers set up the governance of what would become the maquis. The parachuting of weapons, secret agents and radio sets, will change this maquis into a fighting force, equipped with light weapons although without heavy weapons.

A more subtle nuance exists within the Resistance, where the balance of power between civilians and the military, who ensured a common governance of the massif, was often reported, whether it was a question of oppositions between strong personalities or diverging views on the types of actions to be carried out against the occupier.

In their confrontation with the armed resistance organised on the Plateau, the Wehrmacht, the Luftwaffe, the militia and the mobile reserve groups (GMR) applied, often savagely, the law of the strongest.

But, in the words of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “The strongest is never so strong as to be always the master”; the landing of the Allies in Provence will tip the balance of power to the detriment of the occupier and the Vichy government.

Authors: Guy Giraud and Julien Guillon

From mobilisation to action

The decision of Mr. Descour to mobilize the forces of the Vercors is based on criteria for assessing the situation criticized by some. Objectively, however, they respond, on the one hand, to orders received from London, on the other hand, oral or written assurances of Colonel Constant (Saint-Sauveur) of the BCRA and J. Soustelle, head of the secret service in Algiers, on the validity of the Montagnards Project specific to the Vercors.

The number of people mobilised exceeded forecasts, which led to an increased effort in terms of reception and distribution of volunteers in the fighting units.

At the same time, it was decided to apply the military plan of the Montagnards Project, which consisted of locking the accesses to the Vercors. On 13 and 15 June 1944, the first fighting took place at Saint-Nizier-du-Moucherotte.

Author : Guy Giraud

Civilian companies and mobilisation

From February 1943 onwards, the arrival of the first young people fleeing the Obligatory Labour Service (STO) in the Vercors showed the limits of the massif in terms of accommodating camps in the underground. From a logistical point of view, these young people, who were not yet combatants, had to be fed, organised, supervised and even armed later on. Moreover, the security of the camps did not allow for more than 350 to 450 people in total. What to do with the other men who were determined not to leave for Germany? In parallel to the camps, some young people still managed to stay at home or at the home of a relative, or even at their workplace with false identity cards provided thanks to complicities in the town halls. Patiently incorporated clandestinely into “dormant” companies, known as “civilians” or “sedentary”, they constituted six commanded and supervised units capable of being mobilised on order, even if they had little military training.

They were

- the Prévost (Goderville) civilian company, bringing together the Corps Francs of the plateau, based in the Saint-Nizier-du-Moucherotte sector;

- the Paul Brisac civilian company (Belmont) (la compagnie civile Paul Brisac (Belmont), comprising between 180 and 250 men, mainly from Grenoble, which was stationed at Saint-Nizier-du-Moucherotte;

- the Fernand Crouau (Abel) civilian company (la compagnie civile Fernand Crouau (Abel), with around 400 men, mainly from Romans, based at La Balme-de-Rencurel;

- the Ullmann (Philippe) civilian company (la compagnie civile Ullmann (Philippe), composed of thirty men divided into teams of six, deployed in the Coulmes forest;

- the Bordenave (Dufau) civilian company (la compagnie civile Bordenave (Dufau)

- the Bourdeaux company (Fayard), recruited in the Royans region, installed in the Lente forest

- the civilian company Piron (Daniel), which, after several engagements in the Drôme, was assigned to the defence of Presles. Its strength increased from 60 to 126 soldiers.

The Abel and Daniel companies came from the Drôme; the Belmont company from Grenoble; the Philippe company grouped together the civilian companies that had been progressively set up in the northern sector of the Vercors (or Vercors-north, i.e. the Quatre Montagnes sector); the Goderville company included Frankish groups from the Drôme and the Vercors-north. Responding to the mobilisation order of 9 June 1944, they joined their respective places of regrouping in the Vercors. Following the unpredictable influx of other volunteers, they were reinforced with poorly trained, poorly equipped and unarmed men. Everything had to be done, and in a hurry, to train the companies and engage them in accordance with A. Le Ray’s plan, which consisted in particular of locking the accesses to the massif.

After the Liberation, all these units would wear the insignia of the Pioneers and Volunteer Fighters of the Vercors.

Authors: Julien Guillon and Guy Giraud

The rise of the sedentary volunteers in the Vercors

The number of men in the Vercors camps varied between 300 and 450, depending on the severity of the climate, the morale of the men, illness and injuries. Going beyond this number would lead to difficulties in terms of support, security, supervision and equipment, particularly in terms of weapons.

Volunteers therefore stayed at home and in their workplaces. They are grouped into companies that are able to respond to the call for mobilisation on the massif. These units, poorly trained and poorly armed, came from the Drôme (Romans) and the Isère (Grenoble). Some were in the Vercors (Villard-de-Lans, Autrans). They were called “civilian or sedentary companies”. However, “sedentary” free groups, with a small number of soldiers, gathered for a precise mission and then returned to the normality of daily life. When mobilised, they formed a specific company (Compagnie Prévost, Goderville). These fighters were armed after receiving parachute drops.

The Trièves company, commanded by Lieutenant Champon, went up to the Grand-Veymont – Grande Cabane region to ensure its defence, after the German operations of repulsions carried out in the area where it was stationed.

The company of workers worked on the development of the Vassieux-en-Vercors landing ground.

The main units in the Vercors in July 1944

| Units | Head of corps | Area of activity |

| 6th BCA | Battalion Chief Costa de Beauregard (Durieu) | Corrençon, Villard-de-Lans, Méaudre, Autrans |

| 12th BCA | Battalion Chief Ullmann (Philippe) | Rencurel, la Balme-de-Rencurel, Presles… |

| 14th BCA | Captain Bourdeau (Fayard) | Western and south-western edge of the Lente forest |

| 11th Cuir. | Captain Geyer (Thivollet) | Vassieux-en- Vercors A protection squadron is stationed at Saint-Agnan-en-Vercors |

Author : Guy Giraud

The events of July 1944

From time immemorial, people have sought to come together on the occasion of a major event in their community by creating a symbol that characterises their fraternity.

In July 1944, the governance of the Vercors decreed the restoration of the Republic over the entire massif; the Vichy laws were abrogated. The tricolour flag, flanked by the cross of Lorraine and the “V” which means “Victory” and/or “Vercors”, became the symbol.

A real euphoria reigns over the Vercors in defiance of the German presence in Saint-Nizier. The breath of freedom animated the plateau, despite the fears of some people about the consequences of the brutal arrival of the Germans.

The parachuting, at the end of June, of the Chloroform missions of Jedburgh, Eucalyptus and the Operational Group (OG) Justine, with its reduced number of troops, confirmed this optimism.

On the night of the 6th to the 7th July, the Paquebot mission arrived, commanded by Captain Jean Tournissa (Paquebot). It was in charge of setting up a landing field at Vassieux-en-Vercors.

To ensure the security of their communication routes threatened by the forces of the massif, the Germans, well informed, although probably overestimating the means of the Resistance, attacked the Vercors in four directions.

On 21 July, fighting broke out between the maquisards and the Germans at Vassieux-en-Vercors. Vassieux-en-Vercors, the Wall of the Fused at La Chapelle-en-Vercors, the massacre of the wounded at the Grotte de la Luire, are places of memory for the population and the Resistance fighters of the Vercors.

On 23 July at 4 p.m., F. Huet (Hervieux) gave the order for the dispersal of the fighters into the refuge areas of the forests, with a view to resuming the guerrilla actions.

After 24 July, a ferocious repression fell on civilians and fighters.

Authors: Julien Guillon and Guy Giraud

The month of euphoria, the Republic in Vercors

Following the progress of the landing on the 6th of June on the Normandy coast, waiting for the landing in Provence and then the completion of the Vassieux-en-Vercors landing ground generated, rightly or wrongly, a feeling of collective euphoria and impunity. In fact, the massif was free of any enemy presence, with the exception of Saint-Nizier, where its apparatus was lightened.

Yves Farge, Commissioner of the Republic for the R1 region, and the governance of the Vercors decided to restore the Republic to the Vercors. This decision concerns other sectors such as Die for example. In Saint-Martin-en-Vercors, the 14th of July was celebrated according to the republican tradition and gave rise to a taking up of arms in an atmosphere of popular jubilation.

Authors: Guy Giraud and Julien Guillon

The fights

The restoration of the Republic in the Vercors, the celebration of 14 July 1944 in Saint-Martin-en-Vercors, the impressive parachuting of the allies simultaneously and in broad daylight in Vassieux-en-Vercors could not leave the Germans indifferent. Aware of the threat posed by the forces of the massif to their communication routes, the enemy prepared its response. Master of the airspace from the Valence-Chabeuil airfield, he had a great capacity for observation. It strafed and bombed the Vassieux airfield and La Chapelle-en-Vercors.

On 21 July, Generalleutnant Heinrich Niehoff, Kommandant des Heerresgebiets SüdFrankreich (military commander for the South of France) launched operation Unternehmen Vercors by attacking the Vercors from four directions. He achieved a strategic surprise by landing Luftwaffe special forces paratroopers on the Taille-Crayon field in Vassieux on 21 and 23 July.

From the 21st to the 23rd, German paratroopers and maquisards clashed at Vassieux-en-Vercors; other Wehrmacht units advanced by fighting at the Croix-Perrin, on the Pas de la falaise orientale and at Valchevrière.

Authors: Guy Giraud and Julien Guillon

The Grotto of La Luire

The Vercors military hospital was set up, with makeshift resources, at Saint-Martin-en-Vercors, near the command post of F. Huet (Hervieux) and E. Chavant (Clément). It was directed by Doctor Ganimède. There was an annex at Tourtre.

When the German attack began on 21 July, particularly from the Pas de la falaise orientale and above all at Vassieux-en-Vercors, the government decided to try to escape from the hospital to Die. As elements of the Zabel group of the 9th Panzer division approached Die, the operation was abandoned. The hospital took refuge in the Grotte de la Luire. After sorting out the wounded, Ganimède and three doctors assisted by nine nurses treated 37 people, civilians, combatants and four Germans.

On 27 July at 4 p.m., the Germans entered the porch. The occupants were either executed on the spot, shot in Grenoble or deported. An American lieutenant, considered a prisoner of war, was sent to Germany. Three people were released because they were not identified.

Authors: Guy Giraud and Julien Guillon

The dispersal

On 23 July 1944, after 56 hours of fighting, the Vercors massif was taken over by German troops and the Allies in London and Algiers, who were busy on the various fronts, no longer responded to the Resistance fighters’ calls. This situation led the local military command to order the maquis fighters to disperse into small groups in the sheltered areas of the plateau and to let the German wave pass, before regrouping to resume the fight at a later date in less unfavourable times and in forms adapted to the new situation.

How was this order prepared, distributed and executed? With what results? These are the questions addressed here.

Author: Philippe Huet

Sources :

Association nationale des pionniers et combattants volontaires du Vercors (ANPCVV), Le Vercors raconté par ceux qui l’ont vécu, Grenoble, 1990 ;

Huet family archives, including the testimonies of Robert Bennes, Roland Bechmann, Louis Didier-Perrin, Paul Wolfrom, Gilbert Landau;

Darier Albert, Tu prendras les armes, Grenoble, Imprimerie Veyret-Picot, 1974, 492 p. ;

Darier Albert, Tu prendras les armes, preface by General Le Ray, Grenoble, Association nationale des Pionniers du Vercors, 1983, 492 p. ;

Richard Marillier, Issues de secours, Précy-sous-Thil, Ed. L’Armançon, 2000, 117 p. ;

Marc Serratrice, Avoir 20 ans au maquis du Vercors, 1943 – 1944, collection ” Histoire intime “, Avon-les-Roches, Edition Anovi, 2014 ;

Stephen lieutenant (André Valot), Vercors premier maquis de France, Buenos-Aires, Viau, 1946 (reprinted by the Pionniers du Vercors in 1985 and 1991), Stephen lieutenant (André Valot), Vercors premier maquis de France, Grenoble, ANPCVV, 1991, 178 p.

General framework of the dispersal

It is understandable that the extreme diversity of situations of units gathering several thousand combatants spread over more than 2,000 km² – without any means of radio communication, and for some, already well tested by the fighting – led to very different attitudes when faced with the very concrete problems of applying the dispersal order. Places of withdrawal, camouflage, distribution of weapons, water and supplies, German clashes, return to the plain… are all circumstances and themes that require solutions to be adapted to local conditions.

Author: Philippe Huet

Grouped and organised routes

A first option taken by the Maquisards at the time of the dispersion was to remain in organized groups, either on the Plateau in refuge zones, as prescribed by the dispersion order, or, exceptionally, to attempt an exit towards the plain by passing through the mesh of the German encirclement.

The choice to remain on the Plateau was made by units that were already experienced because they were made up of elements that had been in the maquis for several months. This was the case, in particular, for the units of Costa de Beauregard in the north (6th BCA) and Geyer (11th Cuir.) in the south, or even for elements of the civilian companies that were well trained and not much tested by the fighting (Jacquelin(e) and Jansen sections). All these groups were able to stay on the Plateau and survive in extremely difficult conditions, with few or no casualties.

We should also mention the group of Robert Bennes, known as Bob, BCRA officer, head of the radio operators, who received commando training in Staoueli in Algeria, before being parachuted near Vienne. During the dispersal, he spontaneously took the lead of a group that was in Pré-Grandu, at the foot of the Pas de l’Est in the open zone, and led it safely and without losses to Oisans, at the end of a 10-day raid, a real military exploit.

Author: Philippe Huet

The mixed routes

A second option taken by the maquisards at the time of the dispersal was to remain for a time in an organised group on the Plateau in the refuge zones, then to divide up into small teams in order :

- either to attempt an exit from the massif with “more chances” of crossing the enemy encirclement – the fortunes were varied (case of the Potin section, the Prévost Company, Eugène Chavant accompanied by 200 Maquisards, the Jouneau group, Louis-Didier Perrin and his companions);

- or to re-establish links between the units or with the outside world (as in the case of the headquarters) before regrouping the Resistance fighters in the plain.

It seems that these dispersals in two phases (grouped and then in small teams) were frequent, or at least these are the ones for which we have been able to collect the greatest number of testimonies.

Author: Philippe Huet

Individual courses

Alongside the grouped or grouped and then split routes (mixed routes), a third option was taken by some Maquisards during the dispersal, that of going out on their own, either because they had lost contact with their unit, or because they felt that this gave them the best chance of getting out to resume the fight or return home.

The following are examples: Roland Bechmann, aged 24, son-in-law of Jean Prévost, known as Gammon-Lescot, for his skill in handling grenades and other explosive devices, and Paul Wolfrom, aged 18, nephew of Colonel Marcel Descour. Both, at the end of their journey, returned to combat.

Author: Philippe Huet

Massacres and atrocities during the Second World War

Generalleutnant Heinrich Niehoff (1882-1946), military commander of the German army deployed in the South of France (Kommandant des Heeresgebiets SüdFrankreich), initiated the fight against the armed Resistance movements. He advocated a tough approach against the resistance fighters, whom he did not hesitate to describe as “subhuman bandits” (sic).

Units of the Sipo/SD (Sicherheitspolizei und Sicherheitsdienst, literally the security police and the security service) participated independently in the operations.

The German ‘anti-terrorist’ guidelines do not justify the abuses and atrocities committed; they explain their harsh reality. A distinction must be made between

- those killed during the war operations and the dispersal of units, in particular those of the combatants and civilians killed during the Luftwaffe glider assault at Vassieux-en-Vercors, those during the fighting in the Quatre-Montagnes sector, the eastern cliff steps and Valchevrière ;

- beyond these combats, the “savage” execution of wounded maquisards and civilians, men, women and children suspected of supporting the Resistance;

- the inhuman executions of hostages and innocent civilians during the sweep of the massif to sterilise any return of the Resistance to the massif (La Chapelle-en-Vercors, the Luire cave, Cours-Berriat in Grenoble, among other examples).

Author: Guy Giraud

The Vercors maquis, Bir-Hakeim and Oradour-sur-Glane

The Vercors maquis is known both for the fighting that took place there in the summer of 1944 (General Alain Le Ray spoke of “the Battle of the Vercors”) and for the terrible reprisals carried out by the occupying forces following the fighting, which spared neither Resistance fighters, nor civilians, nor livestock, nor houses (the associated literature speaks of “the martyrdom of the Vercors”).

The two aspects are inseparable and constitute, in the words of General Zeller before the World War II History Commission, “the tragic epic of the Vercors”.

This tragedy, “a wound in the side of the Nation and a national pride”, in the words of the Minister Kader Arif, who was present in July 2013 at Vassieux-en-Vercors, has been compared by great witnesses such as General Koenig, hero of Bir-Hakeim, then leader of the FFI, to a “mission of sacrifice”, like Eugène Chavant, civilian leader of the Vercors, in his conference of 6 February 1945 to “a Bir-Hakeim of the Resistance in the metropolis”, like Abbé Pierre to “a first Oradour”, speaking specifically of the repression of the Malleval maquis (maquis de Malleval), of which he was one of the founders. It is this last dark aspect, a consequence of the other aspects, which is discussed in the following documents.

Author: Philippe Huet

Sources :

Patrice Escolan and Lucien Ratel, Guide mémorial du Vercors résistant, Paris, éd. Le Cherche midi, 1994, p. 177.

Archives of the Huet family – Committee for the History of the Second World War, Commission for the History

of the Resistance (Vercors),

first session of 3 February 1961, testimony of General Koenig, typescript, pp. 39-40.